12 hours ago

A New Book of Edward Gorey's Drawings Shows What's Lost When the Artist's Sexuality Is Glossed Over

READ TIME: 7 MIN.

This article is reposted from The Conversation.

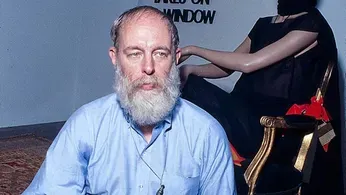

Elizabeth Wolfson, Washington University in St. Louis

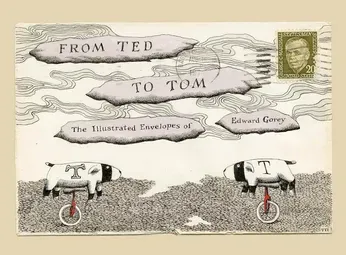

Artist, illustrator and writer Edward Gorey would have turned 100 this year, and the recently published "From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey" is a fitting celebration of his wit and talent.

The book reproduces, in stunning detail, a series of 50 elaborately illustrated envelopes Gorey created in the mid-1970s. But when I started reading "From Ted to Tom," I felt confused – and a little let down.

The book makes no mention of Gorey's queerness. To me, this is a missed opportunity to shed light on how being gay may have fueled some of his most personal work.

The Master of Macabre

Today, Edward Gorey is widely known for his sprawling, macabre-yet-humorous body of work, which spans nearly every medium.

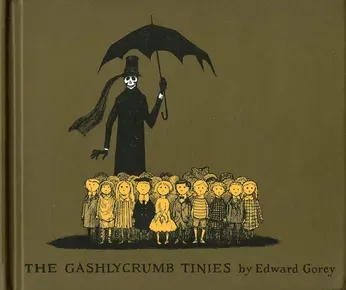

There are dozens of his own books, notably "The Doubtful Guest" and "The Gashlycrumb Tinies," as well as cover designs for many others; sets and costumes for the 1977 Tony Award-winning revival of Bram Stoker's "Dracula"; the opening credit sequence for the PBS television series "Mystery!"; "The Fantod Pack," a deck of Tarot-like cards; and hand-sewn, surrealist dolls.

His stories often feature adults and children alike who meet untimely ends through mostly hilarious, unlikely accidents – and, yes, the occasional straight-up murder. But they're never gratuitous, nor do they glorify violence for violence's sake.

As for his personal life, Gorey may have been what today we'd call asexual; Gorey himself used the term "undersexed," but he also acknowledged, when asked directly about his sexuality, that he "supposed" he was gay.

Mark Dery's 2018 Gorey biography, "Born to be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey," documents the artist's participation in postwar gay life. The book details a handful of crushes Gorey had on various men, at least one of which – a brief affair with a man named Victor – involved some physical intimacy.

To whatever extent Gorey entertained sex or romance, it was with men. As Dery points out, however, this fact largely goes unaddressed in discussions of the artist's work.

Source: Harcourt Brace

A Chance Encounter

"From Ted to Tom" reinforces this silence.

The "Tom" is Tom Fitzharris, the author of the book's introduction and some commentary at the book's end.

In the introduction, Fitzharris explains that before he met Gorey, he was already collecting the artist's "small, exquisite books."

After attending a gallery exhibit of Gorey's work in 1974, Fitzharris mailed him one of the books from his collection to request Gorey's signature, along with a cryptic inquiry about two of the book's characters. Gorey obliged and returned the book with a similarly cryptic reply.

Soon after this exchange, Fitzharris spotted Gorey on the street and introduced himself. The two soon began meeting regularly "for dinner, the theater, coffee, and especially the ballet, his great passion," one that Fitzharris shared. When Gorey left to summer on Cape Cod, he began sending Fitzharris the envelopes collected in "From Ted to Tom."

Fitzharris shares almost no information about himself in the book, and he has never commented publicly about his own sexuality. However, even his dry, minimalist narration cannot conceal the intensity of their connection.

Describing his first visit to Gorey's apartment, he writes: "I thought I'd be at Gorey's for ten minutes, but I left two hours later." Whether Fitzharris lost track of time as the two explored their "dozens of shared interests" or simply couldn't tear himself away, when he finally made it back to work, he was surprised that he still had a job.

Source: New York Review Books

The Envelope as Canvas

Given this voracious drive to create, it is no surprise that Gorey saw an object as humble as a letter envelope as a creative opportunity. As Dery points out, Gorey was also making his illustrated envelopes as the mail art movement was becoming popular. Sparked by artist Ray Johnson in the 1960s – who, like Gorey, lived in New York City – it involved artists using the postal service to exchange works of art, using it as an alternative to the commercial galleries and museums that artists had largely depended on.

The 50 envelopes reproduced in "From Ted to Tom" was not Gorey's first dalliance with the envelope as canvas; he'd experimented with it six years earlier, while in the midst of a collaboration with author and editor Peter Neumeyer, with whom he produced three children's books.

In his drawings to Neumeyer, Gorey mostly seems to be having fun playing around with a new formal challenge: how to integrate drawings with the prerequisite address text in a satisfying way.

Because I study how people use images to make sense of the world, I couldn't help but notice key differences between the Neumeyer envelopes and those that Gorey sent to Fitzharris.

The Fitzharris series is poised and polished from the jump. Gorey's distinctive hand-lettering is crisp, precise and perfectly straight, each envelope a complete scene. Some scenes are more complex than others, but each is a complete thought.

There's another notable difference between the Neumeyer and Fitzharris envelopes. While the former features a revolving cast of real and imaginary creatures, the latter has two co-stars: two black-and-white dogs, sides emblazoned with matching, serifed T's.

In his introduction to the book, Fitzharris confirms that the animals represent Gorey and him. Fitzharris is also clearly more than the lucky witness to a burst of creative genius. He is its muse.

The Envelope as Canvas

Given this voracious drive to create, it is no surprise that Gorey saw an object as humble as a letter envelope as a creative opportunity. As Dery points out, Gorey was also making his illustrated envelopes as the mail art movement was becoming popular. Sparked by artist Ray Johnson in the 1960s – who, like Gorey, lived in New York City – it involved artists using the postal service to exchange works of art, using it as an alternative to the commercial galleries and museums that artists had largely depended on.

The 50 envelopes reproduced in "From Ted to Tom" was not Gorey's first dalliance with the envelope as canvas; he'd experimented with it six years earlier, while in the midst of a collaboration with author and editor Peter Neumeyer, with whom he produced three children's books.

In his drawings to Neumeyer, Gorey mostly seems to be having fun playing around with a new formal challenge: how to integrate drawings with the prerequisite address text in a satisfying way.

Because I study how people use images to make sense of the world, I couldn't help but notice key differences between the Neumeyer envelopes and those that Gorey sent to Fitzharris.

The Fitzharris series is poised and polished from the jump. Gorey's distinctive hand-lettering is crisp, precise and perfectly straight, each envelope a complete scene. Some scenes are more complex than others, but each is a complete thought.

There's another notable difference between the Neumeyer and Fitzharris envelopes. While the former features a revolving cast of real and imaginary creatures, the latter has two co-stars: two black-and-white dogs, sides emblazoned with matching, serifed T's.

In his introduction to the book, Fitzharris confirms that the animals represent Gorey and him. Fitzharris is also clearly more than the lucky witness to a burst of creative genius. He is its muse.